Fine of the Month: September 2010

(David Carpenter)

1. A Peasant in politics during the Montfortian regime of 1264–1265: The Wodard of Kibworth case

In several of his Fine of the Month articles David Carpenter has examined how the lives of the peasantry can be illuminated through analysis of Fine Roll evidence. Here, in taking one now famous example from Kibworth in Leicestershire, he demonstrates the surprising levels of politicisation amongst the unfree and the extent to which national political events played out at the local level.

⁋1The Henry III Fine Rolls Project has shed much light on the way peasant communities offered money to the king, sometimes substantial sums of money, in order to gain privileges and favours. 1 Peasants on royal manors did so in order to have permission to run the manor themselves, free from the interference of the sheriff or some other royal bailiff. Peasants also purchased writs and letters which sought, in various ways, to prevent their lords increasing their customs and services. Such activities, already the subject of several ‘Fines of the Month’, were part of an increasing tide of peasant aspiration and protest which makes the thirteenth century very much the ‘training ground’ for the later ‘Peasants’ Revolt’. 2 This month’s article seeks to add more colour to this picture. It is the story of how a particular peasant, Wodard of Kibworth, demonstrated his support for Simon de Montfort during the period between the battles of Lewes and Evesham in 1264–1265, when Simon was the virtual ruler of England. Wodard’s case has a certain topicality because I came across it when contributing to Michael Wood’s new BBC Four TV Series ‘Story of England’, a history of the Leicestershire village of Kibworth. It is also case on which the fine rolls themselves shed a significant light, partly at one point through their very silence.

⁋2It was last year that Michael Wood asked me to discuss with him some documents in The National Archives relating, amongst other things, to Kibworth in the Montfortian period. This was not difficult to do because (as I was glimpsed saying in the trailer to the programme) ‘this was a highly politicised area’. Simon de Montfort was earl and lord of Leicester (some nine miles north west of Kibworth) and several local knights were drawn, by ties of neighbourhood and tenure, into his following. One of these, as has long been known, was the lord of Kibworth itself, Saer de Harcourt. 3 The area also witnessed a famous example of peasants involving themselves in politics. A few days after Simon de Montfort’s defeat and death at the battle of Evesham in August 1265, a group of peasants from Peatling Magna (six miles west of Kibworth) sought to arrest a party of royalists going through the village, declaring that they were acting ‘against the welfare of the community of the realm and against the barons’, a declaration which shows peasants had grasped the concept of the community of the realm and thought the barons were acting in its interests. 4

⁋3The Peatling Magna episode naturally raised the question of how far there were comparable feelings at Kibworth, a question at first sight not easy to answer because there seemed no evidence on the subject. No evidence, that is, until I began to think harder about the document from which we know that Saer de Harcourt was a knight of Simon de Montfort. Saer’s appearance in this is, in fact, tangential for the document is actually a pardon to Wodard of Kibworth for committing a homicide. Although the letter embodying the pardon was in the king’s name, it was an act of Simon de Montfort, since it was issued on 22 April 1265 during the period when he was ruling England. In the summary of the letter found in the patent rolls, it runs as follows:

⁋4 The King to all people etc. Since we have learnt from an inquiry, which we ordered to be done by our beloved and faithful Gilbert of Preston, that Wodard of Kibworth killed William King in self-defence so that he could not otherwise have avoided his own death, and not by felony and pre-meditated malice, We, at the instance of Saer de Harcourt, knight of our beloved and faithful Simon de Montfort, earl of Leicester and our steward of England, have pardoned the same Wodard the suit of our peace which belongs to us for the aforesaid death, and we have conceded to him our firm peace, provided that he stands to right in our court if anyone wishes to speak against him. In testimony of which we have issued these our letters patent. Witness the King at Northampton 22 April [1265]. 5

-

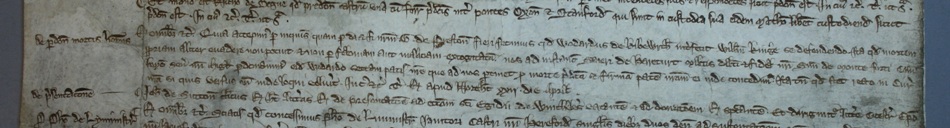

- C 66/83, m. 19. Pardon for Wodard of Kibworth.

⁋5What is remarkable about this pardon is the way it associates Wodard first with Saer de Harcourt, and then by extension, with Simon de Montfort, who is styled not merely earl of Leicester, but also steward of England, a title he was increasingly adopting to give some support to his role as England’s effective ruler. 6 Pardons did not need to mention intercessors. Indeed, one issued only a few days before Wodard’s, after a similar inquiry by the judge, Gilbert of Preston, did not do so. 7 Even when they are mentioned, they are never linked, like Saer, with Simon de Montfort. The letter, therefore, is unique. It was deliberately designed to proclaim Saer’s Montfortianism and also, by extension, Wodard’s too. The mantle of the great earl is thrown over both of them, and in a most public way, for the pardon was embodied in a letter patent, addressed to everybody and designed to be open or ‘patent’, with the king’s seal hanging beneath it by silken thread. One can surely imagine Wodard returning with his pardon to Kibworth and proudly showing it to his fellow villagers, showing them how it joined him both to Saer and to Simon; the peasant, the knightly lord of the manor, and the great earl who was ruling England, the community of the realm encapsulated in a single document.

⁋6In saying all this, I have rather taken for it for granted that Wodard was indeed someone of peasant status, yet this does seem a reasonable assumption. The survey of Kibworth, when it was in the king’s hands after the battle of Evesham, states that eighteen and a half virgates were held in villeinage, each worth 16s. to the lord, whereas the amount of land held freely was small. 8 The survey gives no names, but fortunately there is clear evidence that Wodard was part of the village community and also carried an axe, which is surely the weapon of a peasant rather than of someone higher up the social scale. This brings us on to the events behind Wodard’s pardon, events which provide further evidence of his Montfortianism, and thus help explain why the pardon was framed in the way it was.

⁋7Initially, in discussing the question with Michael Wood, I havered over whether anything more could be discovered about Wodard’s pardon, only then to remember that the roll of cases heard by Gilbert of Preston in 1264–65 survives. Indeed it has been the subject of a paper by Susan Stewart. 9 I, therefore, dashed up to the Map Room at TNA (where medieval documents are delivered to readers), ordered the roll out and found, just as I was beginning to give up hope, the record of the inquiry on membrane 19. It was heard by Preston on 11 April 1265 at Rockingham. The jury had to decide

⁋8‘whether Wodard of Kibworth killed William King of Bowden [Great Bowden, just by Market Harborough] in self defence so that otherwise he could not have escaped his own death, or through felony or premeditated malice.’

⁋9The jury, composed of twelve local men, said on oath that,

⁋10‘When the men of Kibworth came to the church of [Market] Harborough to make their procession there on Monday in the week of Pentecost in year 48 [9 June 1264], according to what is the custom of the country, the foresaid William King came and wished to prevent them from proceeding into the foresaid church, and struck the foresaid Wodard, who came with the foresaid men of Kibworth, in the head with an axe, and pursued him, wishing to strike him again and kill him if he could, and the foresaid Wodard, perceiving this, turned round and struck the foresaid William in the head with an axe so that he afterwards died of that blow. So they say certainly that the foresaid Wodard killed the foresaid William in self defence and not through felony or premeditated malice.’ 10

-

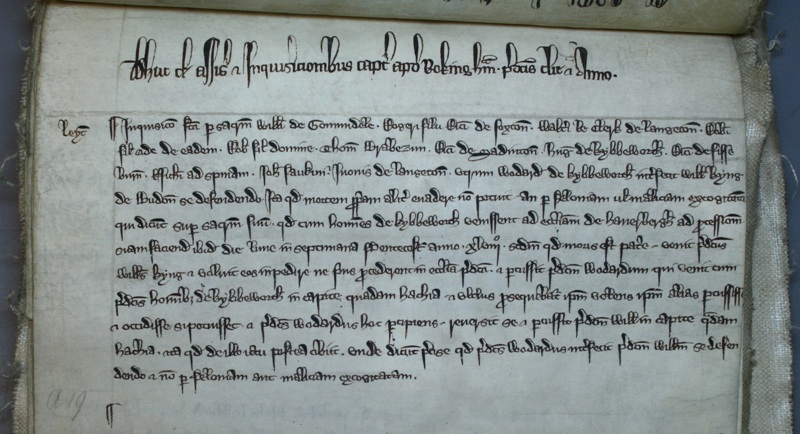

- Just 1/1197, m. 19. Jury verdict on the killing of William King by Wodard of Kibworth in self-defence.

⁋11Now some of the testimony here is formulaic: the danger to one’s life, the flight, the turn to defend oneself, these are found in many such inquiries. On the other hand, the men of Kibworth’s Whit Monday procession to the church of Harborough, some seven miles away, ‘according to the custom of the country’, is clearly unique to this case. 11 The resulting brawl may have had purely local explanations, but I wonder. What is significant is the date: 9 June 1264, only, therefore, four weeks after Montfort’s great victory at the battle of Lewes on 14 May. It seems highly probable that Saer himself, Montfort’s knight, had been with him at the battle, in which case was Wodard there too with a contingent of Kibworthians? If so, what happened on 9 June, perhaps, was that the Kibworthians transformed their traditional Whit Monday procession into a triumphant march, after which they intended to hold a service of celebration and thanksgiving in Harborough church.

⁋12That there was local opposition is not surprising. Peasants had good reason to support Montfort’s cause, since the reform movement had reached out to them both through judicial inquiries and legislation. But, on the other hand, there was also a belief, seen in the offers in the fine rolls, that the king was a good lord who would support peasants against oppression. That feeling may have been especially strong on royal manors, which both Harborough and next door Bowden were. 12 Indeed, given his name, William King of Bowden, perhaps Wodard’s victim had some special connection with the monarch. The early part of 1264, moreover, was a moment when relations between the king and his men of Bowden and Harborough were particularly close. Back in 1257, Henry III had given the manors, during pleasure, to his Welsh ally, Gruffudd ap Gwenwynwyn, only to take them back when the latter defected to Llywelyn. 13 In March 1264, as Henry set up his standard at Oxford before embarking on the civil war, (and here the evidence comes from the fine rolls), he committed the manors to two local men, Adam fitzBernard of Bowden, and Thomas fitzIvo of Harborough. 14 Their subsequent accounts mentioned the expenses incurred for ‘sending diverse people to the king about the affairs of the manors’, 15 business which included loyally paying £4 10d. from the issues of the manor into the King’s wardrobe on 4 April, 16 and a few days later securing letters of protection ‘for the king’s men of Bowden and Harborough’. 17 Clearly the men felt under threat even before the events which led to William King’s death, which was hardly surprising given their position as royalists in an intensely Montfortian area during the outbreak of the civil war. The events of Whit Monday 1264, therefore, show how the national politics of 1264 had stirred up local communities. The Kibworthians, provocatively and pointedly, sought to celebrate the victory at Lewes in the royal church at Harborough, while William King, leading doubtless the men of Harborough, was equally determined to prevent them.

⁋13We can take the story of Wodard a little further. The actual writ which commissioned Gilbert of Preston to hold the inquiry was issued at Canterbury on 6 October 1264. 18 It was issued in the king’s name, but was of course an act of the Montfortian government, which had been based at Canterbury since mid August, taking all possible steps to meet a threatened invasion by the queen. To that end, a vast army had been gathered, with peasant bands summoned from all the villages of England. 19 Kibworth itself is less than ten miles from the Rutland border, and the constable of the Rutland contingent in the army was one John of Kibworth. 20 It seems almost certain that there was also a contingent from Kibworth itself including, we may think, Wodard. That would explain how he was able, doubtless with Saer’s help, to get the writ commissioning the inquiry. It is here that the negative evidence of the fine rolls becomes significant. They are full, at this time, of offers, usually of half a mark, to secure writs commissioning Gilbert of Preston to hear cases. 21 Yet there is no sign that Wodard had to pay money for his writ, which suggests he was being rewarded for his faithful service in the army.

⁋14Preston finally heard Wodard’s case, as we have seen, at Rockingham on 11 April 1265, and the Montfortian government issued the resulting pardon eleven days later at Northampton. That government, however, was now on the slide, and on 4 August 1265 Montfort was defeated and killed at the battle of Evesham. Saer himself survived the battle (if he was there) but he soon found himself imprisoned as the king’s ‘enemy’, and his lands seized. 22 He eventually secured a pardon in July 1267, but his debts to the Jews, forgiven by Montfort, were reinstated, and he was forced to sell Kibworth to the king’s chancellor, Walter of Merton, whence it eventually came to the college Walter had founded in Oxford. 23 It is the wonderful records preserved at Merton College that helped make Michael Wood’s programme possible. There is an intriguing addendum to the story of Walter’s acquisition of Kibworth, which emerged when Michael Wood and I were looking at Saer’s pardon in The National Archives. Saer’s name appears on the patent rolls in a long list of those who had received pardons, yet it is the only one to have a marginal note against it, a note which indicates that this is the pardon granted to Saer. The note is in a different hand to the list, yet one still contemporary. 24 What seems to have happened is that Walter of Merton, about to buy Saer’s properties, wished to make quite sure there was a record of his pardon, since, unless properly pardoned, any alienation made by Saer would be invalid. 25 Accordingly, in control of the patent rolls as chancellor, Walter ordered a clerk to search through them and check that Saer’s pardon was indeed there, the clerk making the marginal note beside the entry when he had found it. No wonder, with this kind of business care, Walter became chancellor of the realm and made a private fortune.

⁋15What finally of Wodard? Did he fight and die alongside Montfort at Evesham? Or did he live into old age, revering the great earl as a saint and treasuring the latter patent which proclaimed their association? Alas the pardon itself is the last I have discovered about him, although more may emerge from unprinted records both at TNA and Merton College. Perhaps now to celebrate his memory, the good villagers of Kibworth will think of reviving their Whitsun walk to the church at Harborough, although one hopes without the fatal consequences which attended the procession of 9 June 1264.

Footnotes

- 1.

- The text here is written up from talks given to the European Medieval Seminar at the Institute of Historical Research in October 2009 and at the Leeds International Medieval Congress in July 2010, and I am grateful for comments made in the subsequent discussions. Richard Cassidy has kindly supplied the images of Wodard’s pardon and the investigation by Gilbert of Preston. My thanks above all go to Michael Wood for asking me about Kibworth in this period and thus setting me on the trail of this remarkable case. Back to context...

- 2.

- See D. Crook, ‘Adam de St. Martin and the king’s tenants of Mansfield 1217–1222’ (FOM for October 2006) and D. Carpenter, ‘ “The greater part of the vill was there.” The struggle of the men of Brampton against their lord, parts I and II’ (FOMS for December 2008 and March 2009) and his ‘The peasants of Rothley in Leicestershire, the Templars and King Henry III’ (FOM for April 2009). Back to context...

- 3.

- J.R. Maddicott, Simon de Montfort (Cambridge, 1994), pp. 61–67, 71. There were two manors in Kibworth, of which Saer was the lord of one, Kibworth Harcourt. The other was Kibworth Beauchamp. Back to context...

- 4.

- Select Cases of Procedure without Writ, ed. H.G. Richardson and G.O. Sayles (Selden Soc, 60, 1941), p. 43. In general, see D.A. Carpenter, ‘English peasants in politics 1258–1267’, Past & Present, 136 (1992), pp. 3–42, reprinted as chapter 17 in the same author’s The Reign of Henry III (London, 1996). Back to context...

- 5.

- TNA (PRO) C 66/83, m. 19 (CPR 1258–66, p. 418). Back to context...

- 6.

- Maddicott, Simon de Montfort, pp. 332–33. Back to context...

- 7.

- CPR 1258–66, p. 418. Back to context...

- 8.

- Cal. Inquisitions Miscellaneous, i, no. 295 (a survey of Kibworth Harcourt, not Kibworth Beauchamp). In the early rentals of Merton College, dating from the 1280s, the majority of the tenants in Kibworth Harcourt were customary, that is unfree, tenants, holding half a virgate of land: R.H. Hilton, ‘Kibworth Harcourt - a Merton College Manor in the Thirteenth and Fourteenth Centuries’, in his Class, Conflict and the Crisis of Feudalism: Essays in Medieval Social History, pp. 1–17, at p. 12. It is possible, however, that Wodard came from Kibworth Beauchamp (where unfree peasants also predominated). In the early fourteenth century taxation returns for Kibworth Beauchamp, ‘Wodard’ appears as a family surname. I hope to do some further research on this point. Back to context...

- 9.

- S. Stewart, ‘A year in the life of a royal justice: Gilbert of Preston’s itinerary July 1264–June 1265’, Thirteenth Century England XII. Proceedings of the Gregynog Conference 2007, ed. J. Burton, P. Schofield and B. Weiler (Woodbridge, 2009), chapter 12. Back to context...

- 10.

- TNA (PRO) Just 1/1197, at m. 19 (http://aalt.law.uh.edu/AALT4/Just1/Just1no1197/aJUST1no1197fronts/IMG_1475.htm). Back to context...

- 11.

- ‘secundum quod moris est patrie’, ‘according what is the custom of the country’. In an email to me on 30 July 2009, Michael Wood suggested that the church in question was actually that of Great Bowden rather than that of Harborough, this because the latter was only a subordinate chapelry of the former. The incident was depicted as taking place at Bowden in the televised programme. This may be right but it is difficult to explain why the jury of twelve local men said the church of Harborough if they meant that of Bowden. It may be precisely because it was not the main church that the Kibworthians were permitted to go there in annual procession. For the villages and their churches, see J.M. Lee and R.A. McKinley, Victoria County History of Leicestershire, v (1964), pp. 38–49, 133–53. Back to context...

- 12.

- The two manors were usually joined together for administrative purposes. Back to context...

- 13.

- CPR 1247–58, pp. 560, 608. Back to context...

- 14.

- CFR 1263–64, no. 86; and see: http://aalt.law.uh.edu/AALT4/H3/E372no109/aE372no109fronts/IMG_9243.htm, a reference I owe to the kindness of Richard Cassidy. Back to context...

- 15.

- http://aalt.law.uh.edu/AALT4/H3/E372no112/aE372no112fronts/IMG_0331.htm. The accounts ran down to Michaelmas 1264. Back to context...

- 16.

- Cal. Liberate Rolls 1267, p. 133. I can only suppose that it was as a result of some Freudian slip that the payment is stated here to have been made into the king’s Wardrobe at Leicester, when it was certainly at this time at Oxford. Back to context...

- 17.

- CPR 1258–66, p. 311. Back to context...

- 18.

- CPR 1258–66, p. 628. Back to context...

- 19.

- Maddicott, Simon de Montfort, pp. 290–91. Back to context...

- 20.

- CR 1261–64, pp. 362, 405. Back to context...

- 21.

- For example, CFR 1263–64, nos. 151, 156–59, 161, 167, 169, 172–73, 179–80, 183–85, 203, 207, 209, 211, 215–16, 233. Back to context...

- 22.

- Cal. Inquisitions Miscellaneous, i, no. 295. Back to context...

- 23.

- CPR 1258–66, p. 628; The Early Rolls of Merton College Oxford, ed. J.R.L. Highfield (Oxford, 1964), pp. 28, 42, 46, 49, 82, 88, 108. Back to context...

- 24.

- The note in not mentioned in the patent roll calendar: CPR 1266–72, p. 150. Back to context...

- 25.

- Of course, Saer had a letter patent proclaiming his pardon, but it was sensible, should this be lost or challenged, to have an official record too on the patent rolls. Back to context...