Fine of the Month: July 2011

(Jeremy Ashbee)

1. 'Gloriette' in Corfe Castle, 1260

This month, in our first fine of the month focusing on architectural history, Jeremy Ashbee, Head Properties Curator at English Heritage, discusses the earliest-known use of the term 'gloriette' in England, occuring at Corfe Castle in 1260-1.

⁋1In late 1260, four Dorset knights made a survey of the state of the royal castles at Sherborne and Corfe in preparation for the arrival of a new keeper, Matthias de la Mare. 1 What they found on both sites was pitiful: a disordered collection of pieces of armour and fixtures for siege engines, kitchen utensils and restraints for prisoners, almost invariably described in their report as rotten or rusty (putrefactas) and unusable (immunitas). The buildings of Sherborne Castle were in a very poor condition, some of them nearing collapse.

⁋2To a student of the documentation of royal castles and manors in the Middle Ages, the scene that the surveyors described in the 1261 Fine Roll is fairly typical. Inventories and dilapidation surveys throughout the kingdom repeatedly listed rotten food stores and useless armaments, kept in buildings with collapsing floors and failing roofs, and in those castles, like Corfe, that the kings were unlikely to visit regularly, even the most important royal chambers and chapels might soon become cluttered with boxes of documents, armaments, ‘jewels’ and clothing. However, as Huw Ridgeway has pointed out in a recent analysis of the same text, the timing of the Dorset survey gives it an especial interest, coming immediately before Henry III’s repudiation of the Provisions of Oxford and resumption of personal rule, an episode in which other castles such as the Tower of London played a central role. It gives a useful corrective to any expectation that either Henry III or his opponents kept castles in perpetual readiness for the next emergency, even at times in which some kind of action may have seemed imminent. 2

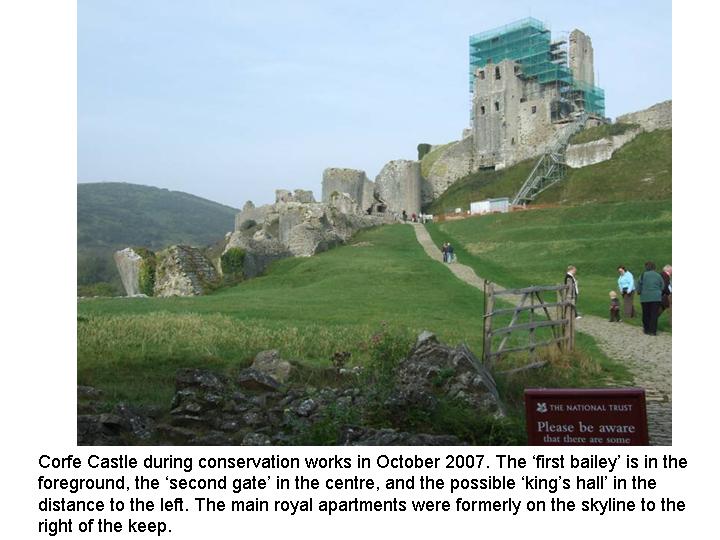

⁋3The survey, particularly in the sections dealing with Corfe, has a further use, in extending our knowledge of the layout and architecture of the castle. 3 Corfe Castle was deliberately ruined by Parliamentarians in 1646 after three years of sieges and though its general plan remains fairly legible, many details of its buildings can now be difficult for the historian to visualise or reconstruct. The 1260 survey lists the items under a number of topographical headings, either individual rooms or buildings, or wider areas within the castle, and several of these can be reconciled with features still visible today. For example, the ‘first bailey of the castle’ (in primo ballio dicti castri), in whose buildings the surveyors found timbers from dismantled siege engines, four tables, tubs and a trough for fishing, is easy to interpret as the present outer bailey, mostly laid out late in the reign of John, though its present gatehouse is a rebuilding of the 1280s. The tower over the second gate (in turri super secundam portam) is likewise identifiable, the building now sometimes called the south-west gatehouse, at the highest point of the outer bailey, south-west of the great Norman keep. On the gatehouse’s upper floor, the surveyors counted a number of crossbows of different materials and methods of operation.

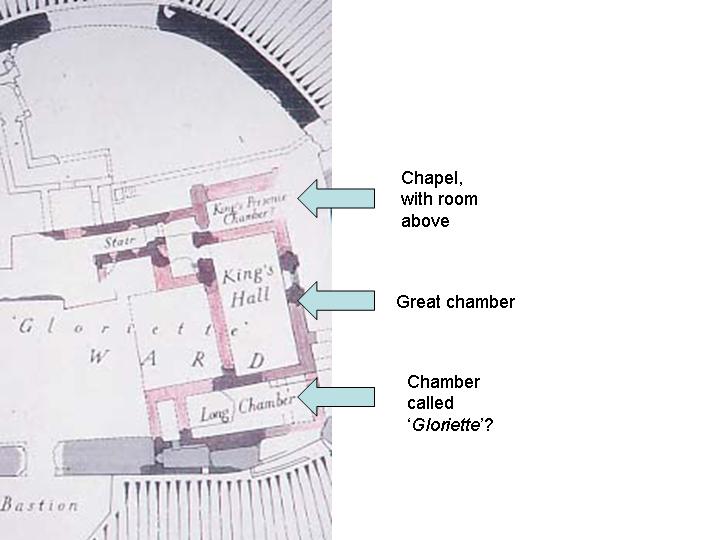

⁋4The other four places in which the knights listed their discoveries undoubtedly lay within the castle’s residential areas further up the hill. The surveyors named them as the ‘king’s hall’ (aula regis), the ‘head of the great chamber’ (in capite magne camere), the ‘storey over the chapel at the head of the great chamber’ (in stagio super capellam in capite magne camere) and, most enigmatic of all, ‘the chamber that is called Gloriette’ (in camera que vocatur Gloriette).

⁋5The king’s hall, given over in 1261 to large timbers including disarticulated pieces of a mangonel (a stone-throwing siege engine powered by men pulling on ropes), appears in numerous other documents of the later thirteenth and early fourteenth century, but cannot be located conclusively today. 4 It may possibly be the ancient structure, containing herringbone masonry probably of the eleventh century, of which fragments survive in the western bailey.

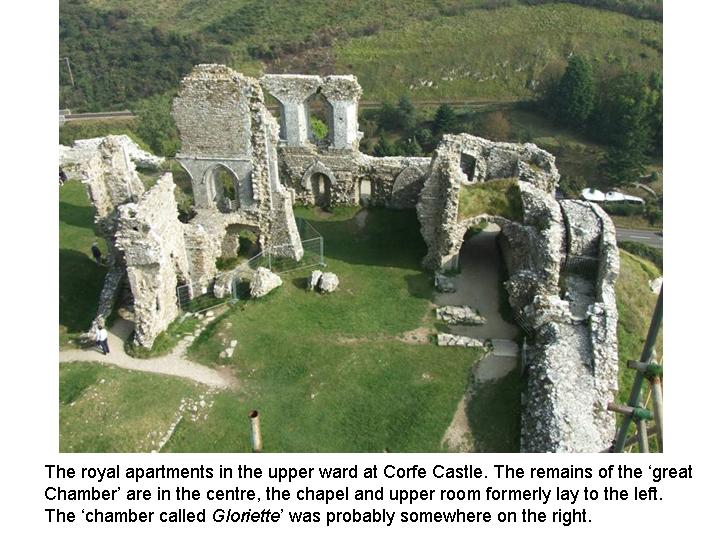

⁋6The other three may be identified more confidently as rooms within the complex at the north-eastern corner of the castle, the highest point of the site. Here may be found the shattered but still impressive remains of a suite of buildings, first constructed by King John in the first years of the thirteenth century, now collectively known by the name ‘Gloriette’. 5 The survey in the 1261 Fine Roll is helpfully precise in describing the one part of the structure that now survives completely enough for its form to be understood: the area at its north-eastern corner. The standing masonry shows clearly that a medieval visitor to the building climbed a stone stair inside a covered porch, rising eastward to the level of the first floor. This brought him to a landing on the middle floor of a three-storey tower, in which he was faced with two finely moulded doorways standing side-by-side, each leading into a different room inside the main body of the building. The right-hand door led into a long rectangular room running north-south, flanked by four tall windows on each long side and open to its timber roof, nearly 20 feet above the floor. By contrast, the room inside the left-hand door was much smaller and comparatively low, covered by a stone rib-vault, with evidence for a room above it, and was orientated east-west. The Fine Roll helps to identify these rooms as respectively the ‘great chamber’ and the chapel, the latter standing ‘at the head’ (north end) of the great chamber and, just as the document states, with another storey above it. 6

⁋7Though only fragmentary traces survive, both attached to the building and lying on the ground beside it, the chapel can be seen today as a very elegant work of architecture; however, the state of neglect that the surveyors found in 1260, with torn vestments and hand-towels, was prefigured long before in 1228, when Henry III needed to command the removal of chests of Exchequer rolls from the chapel and 13 coffers with other documents and jewels from the room above its vault. 7 It is impossible to see today exactly how this upper room was originally entered – a narrow spiral stair in the lost corner of the entrance tower is a possibility – but it must always have been a dead-end, off the main routes through the castle, and its use as a junk room would have caused little inconvenience (except to the chaplain, for whom it was perhaps originally built). Being so hard to reach, in 1260 it contained nothing too bulky to be manoeuvred through narrow stairs or passageways into the room: items of body armour, chains and cuffs for prisoners, liturgical vessels and vestments for the chapel, pots and pans for the kitchen, and only the slings for a siege-engine. By contrast the heavy chests filled with quarrels for the crossbows remained downstairs in the great chamber.

⁋8The final space that the survey mentions is the ‘chamber called Gloriette’. The appearance of this term at Corfe and elsewhere was extensively discussed in an article of 2005; 8 the main findings are hopefully still valid and will be summarised below. The Fine Roll however shows that two of the assumptions made in that paper were incorrect. First, the use of the name in 1261 is a decade earlier than the first instance of the word recorded in Britain hitherto (in an account for Chepstow Castle in 1271), 9 and two decades before its next appearance at Corfe. 10 This appearance in 1261 gives the lie to the suggestion made in the paper that Edward I or his wife was personally responsible for introducing it into English culture. Second, it had been suggested that the room called Gloriette at Corfe was the same as the ‘great chamber’, the large room occupying most of the east range in the complex. A few years ago, this seemed a reasonable assumption: fourteenth-century accounts showed that by the late 1350s, the whole complex had been re-named Gloriette in honour of the original single room, 11 and since the great chamber was by far the largest room identifiable from the surviving fabric, it appeared to be the most likely candidate. By presenting them as two separate items in a list, the 1261 Fine Roll proves that Gloriette and the great chamber were two different rooms.

⁋9Disappointingly it seems likely that little or nothing has survived today of ‘the room named Gloriette.’ Certainly much of the medieval complex in this part of the site has disappeared; if there was ever a western range, this has vanished without trace, and of the medieval range along the south side of the building, only parts of the basement are now still standing, with almost nothing of the first floor, where the main apartments lay. As to the location of Gloriette, it is therefore necessary to speculate: a site somewhere in this south range (originally on the skyline, when viewed from the outer bailey, and with windows giving fine views towards the south), has considerable appeal. But wherever it was, it is surely reasonable to infer that there was something remarkable about Gloriette, causing it to give its name to the whole building, and since this was evidently not a matter of size, or even the importance of its occupant (Gloriette was probably not the king’s or the queen’s own chamber), 12 its receiving this singular honour may perhaps have been a response to an outstandingly lavish decoration or furnishing in the room. A summary in this paper’s final section of the meaning and derivation of the word may lead us to speculate what form this might have taken.

⁋10 Gloriette (or variant spellings such as Gloriet, Gloryette and Glorieth) was adopted as the name of one particular chamber in a small number of high-status residences from the thirteenth century onwards: these were the royal castles at Corfe and Leeds, 13 the castle of the earl of Norfolk at Chepstow, 14 and the lodgings of the prior of Canterbury, standing to the north of Canterbury Cathedral. 15 Other medieval examples from the continent of Europe include a room built in the 1290s for the Count of Artois either in or near the castle of Hesdin, 16 and towers at Arbois and Lillebonne. 17 The documentation for the room called Gloriete in Hesdin is especially evocative, with accounts for extensive wall-painting, many glazed windows, banners on the roof, an aviary of live birds and from at least the mid-fourteenth century, an automaton in the form of a tree, with painted branches, leaves and birds, the latter to squirt water at the unsuspecting. All of the rooms bearing this name thus belonged to individuals of the very highest rank, probably suggesting that their architecture and design were of comparably high quality, and in most cases, there are suggestions in the accounts and in the patterns of use for their sites that they were built as accommodation or for the entertainment of important guests. Given the outstandingly fine stonework of King John’s buildings in this part of Corfe Castle, and its high position with commanding views towards Poole Harbour in one direction and the south coast in the other, the building at Corfe fits well within this group.

⁋11The use of the name Gloriette in northern Europe has a very complicated pedigree, and is now thought to be derived from a twelfth-century chanson de geste, la Prise d’Orange, in which the heroic knight William captures the city of Orange from the Saracens. 18 Much of the action of the chanson takes place in the Saracen palace named Gloriete, a fantastical marble tower with fixtures in gold and silver including silver windows, with luxuriant gardens pervaded with the odour of spices, and labyrinthine passages and dungeons beneath. Inside Gloriete, William meets and woos the beautiful Saracen princess Orable who immediately converts to Christianity, saving him and his accomplices from many terrible deaths, finally helping him to open the city gates to allow the Frankish armies to ride to his rescue. The cycle of chansons featuring William had among the widest circulations of any such collections throughout Europe, and the knight’s adventures can be seen in a few surviving wall-paintings, as in the Tour Ferrande at Pernes-les-Fontaines in Vaucluse. Here William is shown fighting a Saracen in exactly the same way that Henry III would command the depiction of Richard I and Saladin.

⁋12The Fine Roll confirms that the mythology of Gloriette was already current in the time of Henry III, or even of his father King John, who first built the ranges inside which the room lay. Certainly the preference for King John, expressed by Matthew Reeve and Malcolm Thurlby, now seems entirely plausible, but Henry III’s well-known commissioning of motifs with secular themes in his domestic wall-paintings and tiled pavements, such as the depictions of Alexander at Clarendon and Nottingham Castle, or the numerous scenes of ‘Antioch’, showing King Richard’s duel against Saladin, must make it equally likely that it was he who adopted the name at Corfe. The recent identification of the use of the word in the 1261 Fine Roll urges caution against claiming that Corfe was the first place in England where it was used: there may well be earlier instances lying un-noticed in the archives. Yet looking forward, it is certain that Henry’s successors cultivated the legend of Gloriette, building new structures to which they gave the name, and inspiring some of their subjects to do the same. The story’s connotations of heroism and opulence clearly retained their appeal. The use of the chamber called Gloriette in 1260 to store 29 parts from decaying crossbows and six rotten and useless tubs was, like Henry III’s wider fortunes at this time, only a temporary setback.

1.2. C 60/58, Fine Roll 45 Henry III (28 October 1260–27 October 1261), membrane 16d

1.2.1. 198

⁋1[No date]. Concerning the state of castles. This is the view of the state of the castle of Sherborne made by William de Mohun, John de Stroude, John de Cedindon’ and Robert de Godmaniston’, knights, who found there nine iron hauberks that had rusted and five small hauberks all rusted, one brass pot (ollam eream pannam), two pairs of iron buxarum, three helmets and a cap. Moreover, they found all buildings, walls and everything else in a ruinous state (in debili statu).This is the view of the castle of Corfe made by William de Mohun, John de Cedindon’, Thomas de Goshull’ and Robert de Godmaneston’, knights, who found there on the platform above the chapel at the top of the great chamber two rusty hauberks, three pairs of large, rusty iron caparisons, 30 rusty iron caps, 25 rusty helmets, 25 pairs of buxarum for keeping the prisons, 14 pairs of grissilonum, eleven pairs of iron anulorum for keeping the prison, five rusty and immunitas slings for the mangonel, two iron circos, two old brass pans, an old, broken copper pot, three lead vessels for the kitchen, one silver chalice for the chapel, two old and torn towels, one old and torn pair of vestments, two iron chairs, four iron baculos and two large iron chains in the tower above the second gate, 15 horn bows with stirrup and two horn crossbows with stirrup. Item, seven horn bows operated by winch without tiller, two bows with two stirrups without tiller. Item, six wooden crossbows operated by winch. Item, 17 wooden crossbows with stirrup and one with winch. In the king’s hall 25 pieces of timber for the mangonel and two large wooden beams, at the top of the great chamber 26000 quarrels in three arks, both for winch-operated bows and for those with one and two stirrups. In the chamber that is called Gloriette 29 pieces, both bows and tillers, for crossbows, which had rusted, with six rusty and also immunitis winches. In the inner bailey of the said castle, 14 pieces of timber with two wooden beams for the uprights of engines, one trough for fishing with two cunis (?) and four tables. Mathias de Mara received the aforesaid castles in the aforesaid form.

Footnotes

- 1.

- CFR 1260–61, no. 198. Back to context...

- 2.

- H. Ridgeway, ‘Sherborne and Corfe castles, 1260-61’, Fine of the Month, December 2010. Back to context...

- 3.

- Royal Commission on the Historical Monuments of England, hereafter RCHME, An Inventory of the Historical Monuments in the County of Dorset, volume two, South-East, part 1 (London, 1970), pp. 57-78. The RCHME survey remains the most useful description in print of the fabric of the castle, though numerous points of interpretation, particularly the assignation of names to rooms and buildings, have not stood the test of time. Back to context...

- 4.

- e.g. TNA E101/460/27 (repairs, 8-10 Edward I), C145/102 no. 4 (inquisition, 19 Edward II). Back to context...

- 5.

- For a recent discussion of the architecture of this complex, see M. M. Reeve and M. Thurlby, ‘King John’s Gloriette at Corfe Castle’, Journal of the Society of Architectural Historians, 64, no. 2 (June, 2005), pp. 168-85. Back to context...

- 6.

- RCHME mis-labels the chapel as ‘presence chamber’: its identification as a chapel is discussed in J. Ashbee, ‘‘The Chamber called Gloriette’: Living at Leisure in Thirteenth and Fourteenth-Century Castles’, Journal of the British Archaeological Association, 157 (2004), pp. 17-40. Documents corroborating the identification of a chapel in this location include TNA E101/460/27, ‘the stair in front of Saint Mary’s chapel in the upper donjon’, the last word having its usual contemporary sense of an area reserved for the lord, and E101/461/1 (account 31 Edward III) ‘the chapel at the entrance to la Gloriet.’ Back to context...

- 7.

- Calendar of the Patent Rolls of King Henry III 1225-1232 (London, 1903), p. 189. Back to context...

- 8.

- J. Ashbee, ‘The Chamber called Gloriette’. Back to context...

- 9.

- TNA SC6/921/21. Back to context...

- 10.

- TNA E101/460/27, passim. Back to context...

- 11.

- For example, TNA E101/460/30 (account, 30 Edward III) refers to various rooms and buildings including a kitchen and the king’s chamber as lying in le Gloriet; see also note 6 above. Back to context...

- 12.

- TNA E101/460/27 rot. 1 m.2 contains ‘the chamber called Gloriette’, the lord king’s chamber, the lady the queen’s chamber, the chapel and the gate in front of the great tower as separate items in a list of buildings whose roofs were under repair. Back to context...

- 13.

- C. Wykeham Martin, The History and Description of Leeds Castle, Kent (Westminster, 1869), passim; TNA E372/146 rot. 44, m.2d., E372/147 rot. 16d. Back to context...

- 14.

- R. Turner, S. Priestley, N. Coldstream and B. Sale, ‘The ‘Gloriette’ in the Lower Bailey’ in R. Turner and A. Johnson (eds) Chepstow Castle. Its History and Buildings (Logaston, 2006), pp. 135-50. Back to context...

- 15.

- M. Sparks, Canterbury Cathedral Precincts. A Historical Survey (Canterbury, 2007), pp. 51-54. Back to context...

- 16.

- A. Hagopian van Buren, ‘Reality and Literary Romance in the Park of Hesdin’ in E. B. Macdougall (ed.) Medieval Gardens (Washington DC, 1986), pp. 115-34, especially p. 122, n. 16. Back to context...

- 17.

- J. Mesqui, Le Chateau de Lillebonne des Ducs de Normandie aux Ducs de Harcourt. Mémoires de la Société des Antiquaires de Normandie, 13 (2008), pp. 26-28. Back to context...

- 18.

- For an English translation, see J. M. Ferrante (ed.) Guillaume d’Orange. Four Twelfth-Century Epics (New York and London, 1974). Back to context...